There is only One cast,the cast of humanity.

There is only One religion,the religion of love

There is only One language, the language of the heart.

There is only One God and He is omnipresent.

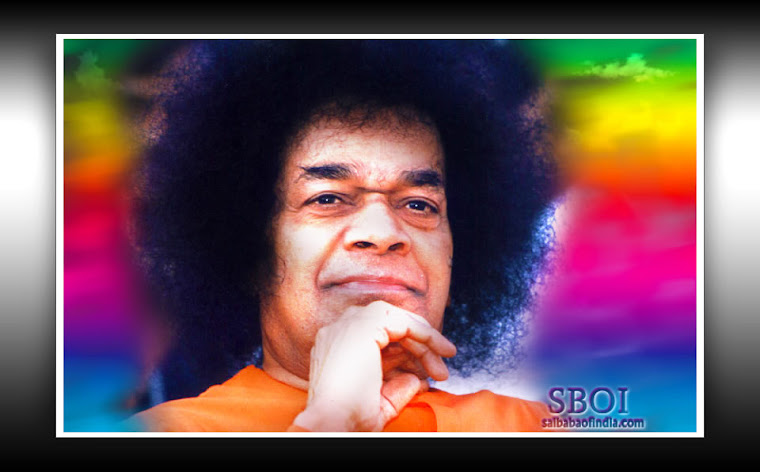

Baba

Υπαρχει μονο Μια φυλη,η φυλη της ανθρωποτητας.

Υπαρχει μονο Μια θρησκεια,η θρησκεια της αγαπης.

Υπαρχει μονο Μια γλωσσα,η γλωσσα της καρδιας.

Υπαρχει μονο Ενας Θεος και ειναι πανταχου παρων.

Μπαμπα

Let it be light between us,brothers and sisters from the Earth.Let it be love between all living beings on this

Galaxy.Let it be peace between all various races and species.We love you infinitely.

I am SaLuSa from Sirius

Channel:Laura/Multidimensional Ocean

Ειθε να υπαρχει φως αναμεσα μας, αδελφοι και αδελφες μας απο την Γη .Ειθε να υπαρχει αγαπη

αναμεσα σε ολες τις υπαρξεις στον Γαλαξια.Ειθε να υπαρχει ειρηνη αναμεσα σε ολες τις διαφο-

ρετικες φυλες και ειδη.Η αγαπη μας για σας ειναι απειρη.

Ειμαι ο ΣαΛουΣα απο τον Σειριο.

Καναλι:Laura/Multidimensional Ocean

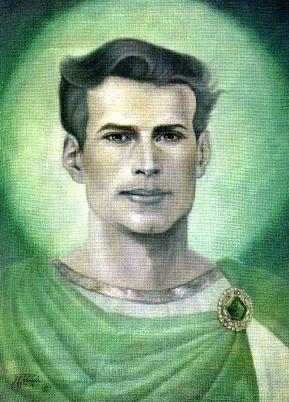

SANAT KUMARA REGENT LORD OF THE WORLD

SANAT KUMARA

REGENT LORD OF THE WORLD

The Ascended Master SANAT KUMARA is a Hierarch of VENUS.

Since then SANAT KUMARA has visited PLANET EARTH and SHAMBALLA often.SANAT KUMARA is sanskrit and it means"always a youth". 2.5 million years ago during earth's darkest hour, SANAT KUMARA came here to keep the threefold flame of Life on behalf of earth's people. After Sanat Kumara made his commitment to come to earth 144.000 souls from Venus volunteered to come with him to support his mission.Four hundred were sent ahead to build the magnificent retreat of SHAMBALLA on an island in the Gobi Sea.Taj Mahal - Shamballa in a smaller scaleSanat Kumara resided in this physical retreat, but he did not take on a physical body such as the bodies we wear today. Later Shamballa was withdrawn to the etheric octave, and the area became a desert.Gobi DesertSANAT KUMARA is THE ANCIENT OF DAYS in The Book of DANIEL.DANIEL wrote (19, 20):"I beheld till the thrones were set in place, and THE ANCIENT OF DAYS did sit, whose garment was white as snow, and the hair of his head like the pure wool. His throne Always like the fiery flame and is wheels as burning fire. [His chakras.]"A fiery stream issued and came forth from before him.Thousand and thousands ministered unto him, and ten thousand times and ten thousand stood before him."I saw in the night visions, and, behold, one like THE SON OF MAN came with the clouds of heaven, and came to THE ANCIENT OF DAYS, and they brought him near before him."And there was given him dominion and glory and a kingdom, that all people, nations and languages should serve him.His dominion is an everlasting dominion, which shall not pass away, and his kingdom that which shall not be destroyed." The supreme God of Zoroastrianism, AHURA MAZDA is also SANAT KUMARA.In Buddhism, there is a great god known as BRAHMA SANAM-KUMARA, yet another name for SANAT KUMARA.SANAT KUMARA is one of the SEVEN HOLY KUMARAS.The twinflame of SANT KUMARA is VENUS, the goddess of LOVE and BEAUTY.In 1956, SANAT KUMARA returned to Venus, and GAUTAMA BUDDHA is now LORD OF THE WORLD and SANAT KUMARA is REGENT LORD OF THE WORLD.SANAT KUMARA`s keynote is the main theme of Finlandia by SIBELIUS.

The Ascended Master Hilarion Healing and Truth

The Ascended Master Hilarion - Healing and Truth

The Ascended Master of the Healing Ray

The ascended master Hilarion, the Chohan,1 or Lord, of the Fifth Ray of Science, Healing and Truth, holds a world balance for truth from his etheric retreat, known as the Temple of Truth, over the island of Crete. The island was an historic focal point for the Oracle of Delphi in ancient Greece.We know few of this master’s incarnations, but the three most prominent are as the High Priest of the Temple of Truth on Atlantis; then as Paul, beloved apostle of Jesus; and as Hilarion, the great saint and healer, performer of miracles, who founded monasticism in Palestine. Embodied as Saul of Tarsus during the rise of Jesus’ popularity, Saul became a determined persecutor of Christians, originally seeing them as a rebellious faction and a danger to the government and society. Saul consented to the stoning of Stephen, a disciple of Jesus, failing to recognize the light in this saint and in the Christian movement.jesus had already resurrected and ascended2 when he met Saul on the road to Damascus. And what an electrifying meeting that was! “It is hard for thee to kick against the pricks,”3 Jesus uttered to an awestruck Saul. Blinded by the light that surrounded the form of Jesus, Saul crumpled to the ground. Not only his body but his pride was taken down a few notches that day.This was the most famous of Christian conversions, whereupon Saul became the mightiest of the apostles. Saul took the name Paul and resolved to spread the word of truth throughout the Mediterranean and the Middle East. Paul had inwardly remembered his vow to serve the light of Christ—a vow that he had taken before his current incarnation. Three years after conversion, Paul spent another three years in seclusion in the Arabian Desert where he was taken up into Jesus’ etheric retreat. Paul did not ascend in that life due to his torturing of Christians earlier in that embodiment. In his very next lifetime, Paul was born to pagan parents in 290 A.D. They resided in the same geographical region in which he had lived as Paul in his previous lifetime. As a young boy, Hilarion was sent to Alexandria to study. During this time of study, he heard the gospel and was converted to Christianity.His greatest desire was to be a hermit—to spend his time fasting and praying to God in seclusion. So he divided his fortune among the poor and set out for the desert near Gaza. He spent twenty years in prayer in the desert before he performed his first miracle. God, through him, cured a woman of barrenness. And his healing ministry began.Soon Hilarion was sought out by hundreds who had heard of his miraculous cures and ability to exorcise demons. In 329 A.D., with a growing number of disciples assembling around him, he fled to Egypt to escape the constant flow of people seeking to be healed from all manner of diseases. His travels brought him to Alexandria again, to the Libyan Desert and to Sicily.But his miracles did not only include healings. Once when a seacoast town in which he was staying was threatened with a violent storm, he etched three signs of the cross into the sand at his feet then stood with hands raised toward the oncoming waves and held the sea at bay.Hilarion spent his last years in a lonely cave on Cyprus. He was canonized by the Catholic Church and is today known as the founder of the anchorite life, having originated in Palestine. To this day, those known as anchorites devote themselves to lives of seclusion and prayer. Hilarion ascended at the close of that embodiment. Hilarion, as an ascended master, speaks to us today of the power of truth to heal the souls of men, delivering his word through The Hearts Center’s Messenger, David Christopher Lewis. Current teachings released from Hilarion include the following:

· On the power of healing: Hilarion teaches his students that “[t]he power of healing is within your Solar Source.” He gives his students “an impetus, a spiral of light that you may fulfill your mission…” and exhorts them to “use this spiral of light for the benefit of sentient beings”. —July 2008

· On the power of joy: Hilarion encourages us to “experience the pulsation of joy” and shows each of us the joyous outcome of our life, which is “a life lived in joy.” He assures us, “I will always lead you to your freedom to be joy”. —June 2008

· On the love of truth: Hilarion teaches that the love of truth will enable us to see clearly the light that is within us. He teaches that instead of criticizing, we must go within and eliminate the particles of untruth within ourselves. —February 2008

· On the action of solar light: Hilarion delivers a greater action of solar light to help release all past awareness of lives lived outside divine awareness. He explains his ongoing mission over many lifetimes—to heal by the power of each soul’s recognition of the truth of her own divinity—and pronounces, “I am the messenger of healing and joy to all. May your life as a God-realized solar being be bright-shining ever with the aura of the truth who you are in my heart.” —March 14, 2008

1. “Chohan” is a Sanskrit word for “chief” or “lord.” A chohan is the spiritual leader of great attainment who works with mankind from the ascended state. There are seven chohans for the earth—El Morya, Lanto, Paul the Venetian, Serapis Bey, Hilarion, Nada and Saint Germain.back to Chohan…

2. The ascension is complete liberation from the rounds of karma and rebirth. In the ascension process, the soul becomes merged with her Solar Presence, experiencing freedom from the gravitational, or karmic, pull of the Earth and entering God’s eternal Presence of divine love. Students of the ascended masters work toward their ascension by studying and internalizing the teachings, serving life, and invoking the light of God into their lives. Their goal as they walk the earth is the cultivation of a relationship with God that becomes more real, more vital with each passing day.back to ascended…

3. Acts 9:5 back to kick against the pricks…

The Ascended Master Saint Germain

The Ascended Master Saint Germain

I have stood in the Great Hall in the Great Central Sun. I have petitioned the Lords of Karma to release Dispensation after Dispensation for the Sons and Daughters of God and, yes, for the Torch Bearers of The Temple. Countless times I have come to your assistance with a release of Violet Flame sufficient to clear all debris from your consciousness. Numberless times I have engaged the Love of my Heart to embrace you, to comfort you, to assist you when you have not known which way to turn.

"I merely ask you to keep the watch, to hold fast to the Heart Flame of your own God Presence, to understand that your first allegiance is to the Mighty I AM. That you have no other Gods before the I AM THAT I AM.

through the Anointed Representative®, Carolyn Louise Shearer, February 14, 2007, Tucson, Arizona U.S.A. (10)

Blogroll

- Ammach Spring Conf 2013 Marie Kayali

- UFO's & ALIENS TRUTH (Greek community)

- deus nexus

- Kauilapele's Blog

- American Kabuki

- Portal 2012 The Intelligence Hub for the Victory of Light

- Obi Wan Kabuki

- Removing The Shackles

- Exopolitics institute

- James Gilliland - Eceti

- Lucas2012 Infos

- 2012 How is it Happening?

- Acheiving World Peace Now!

- Aquarius Channelings

- BeforeItsNews

- Awakening to the DIVINE

- Beyond Ascension

- Bill Wood's website

- Carol Roisin's website – non weaponization of space.

- Cosmic Paradigm

- Cosmic Vision News

- David Wilcok

- Despertando

- dreamwalkerdiaries

- Divine Cosmos

- Dreamweaver333

- Here and Now(2012 Indy Info)

- Kp40 Here and Now

- KaliedoScopeVisions

- Laura Tyco | Lightworkers

- Mike Quinsey on Tree of the Golden Light

- Oracles and Healers

- Pleiadedolphininfos – Meline LaFont

- Religion and Love

- Reptilian Agenda David Icke

- SHELDAN NIDLE UPDATES

- Spirit Train Chronicles

- Stephen Cook hosts The Light Agenda

- The 2012 Scenario

- The Angel Diaries

- The Art of Universal Knowing

- The Galactic Free Press

- The Golden Age Daily

- The Rainbow Scribe

- UFO Hypotheses